Move over, Billy Jean King! While you are awesome, Mazatlán’s own Margarita Montes won 28 of her 33 professional boxing matches against men—and that was back in the 1920s! She is perhaps the only Sinaloan woman to be interviewed by Ripley himself for his Believe It or Not, and was also interviewed by the French magazine Liberation for her life as a feminist.

Move over, Billy Jean King! While you are awesome, Mazatlán’s own Margarita Montes won 28 of her 33 professional boxing matches against men—and that was back in the 1920s! She is perhaps the only Sinaloan woman to be interviewed by Ripley himself for his Believe It or Not, and was also interviewed by the French magazine Liberation for her life as a feminist.

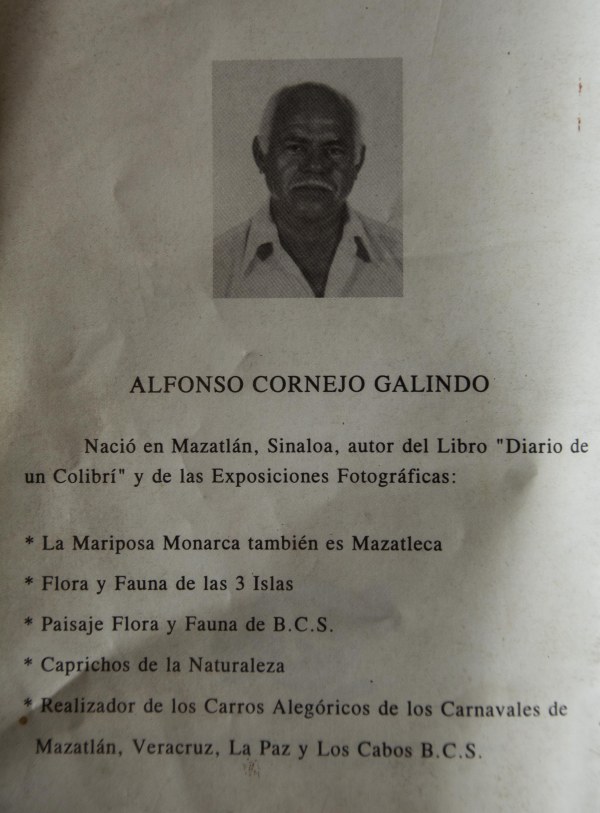

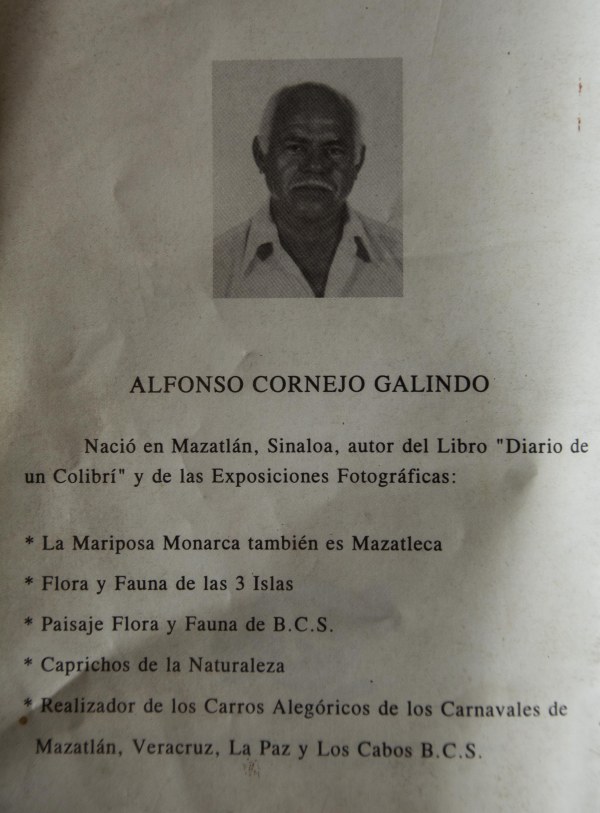

In an era when women were expected to be quiet, submissive and obedient, “La Maya,” as she was affectionately called, was anything but. Born with the need to achieve and be seen, she excelled in several sports and fought for women’s rights long before it was cool. The sixth of eight children of a poor farming family, La Maya was a baseball player (state champion pitcher in 1929), boxer (Pacific League champion), bullfighter, mechanic and pig hauler; she owned a traveling movie theater, a tortillería and a bicycle repair shop; and she was a wife, mother, grandmother and friend. Sadly, she died before I was able to meet her, in 2007. Last night, however, I saw her house and met the man who recorded her oral history back in 1997, when La Maya was 82 years old—local writer, photographer and Carnaval float designer, Alfonso (Poncho) Cornejo Galindo.

La Maya’s former house on Calle Rosales in El Centro.

The author today, in a throne from a Carnaval float.

I recently read his booklet, and it is a fantastic story! The photos in this article are taken from that story, and the contents are a summary in English of the Spanish text, shared with all of you with Poncho’s permission.

Margarita got her nickname, “La Maya,” from her father because he hair always hung in her face as a child. In the book she narrates her own story. She tells us she was born in the small town near Mazatlán called Chilillos. Her father cut himself with a machete and came to a hospital in Mazatlán, where he decided to move the family, in 1917 or so. The children had never before seen cars. La Maya remembers her sister Pachita and her arriving into town at sunset on a burro. She played as a child amongst the corrals of cattle on Rosales street, where the PRI building now stands.

Poverty taught her that to win she had to fight hard, to stand out she had to overcome, and she especially wanted to overcome the condition of being a submissive, quiet, obedient woman. She tells us she was always very motivated to overcome the obstacle of the difference between the sexes.

La Maya only went to school through first grade. She learned to spell a bit, but there were so many kids that they had to work to eat. At 12 she started to work in the nixtamal mill of Mr. Xicotencatle del Valle.

She tells us she was a wild child. Her father tried to change her, but her destiny was decided. She had a fever inside motivating her to do something! They used pieces of canvas to make baseball mitts, and silk stockings to make the balls, which they then covered with a milky juice that hardened over the balls. The bat they used was a tree branch, formed with a machete. She had a good arm and pitched very hard. She remembers that she was a sore loser who couldn’t stand losing. Strength, muscles and triumph were her goals.

Delfina worked with her at the mill and lived near the baseball stadium, where the Escuela Nautica is now. She insisted La Maya go with her to play baseball, but La Maya’s dad wouldn’t let her. She then invited a neighbor to go with her one afternoon, and they went without telling anyone. The team members loaned La Maya a real glove that fit so well, and a real ball that caressed her hand, unlike what they had in the barrio.

Delfina worked with her at the mill and lived near the baseball stadium, where the Escuela Nautica is now. She insisted La Maya go with her to play baseball, but La Maya’s dad wouldn’t let her. She then invited a neighbor to go with her one afternoon, and they went without telling anyone. The team members loaned La Maya a real glove that fit so well, and a real ball that caressed her hand, unlike what they had in the barrio.

They named La Maya pitcher on that very first day. It was the first time she felt she could be successful, break barriers, that her restlessness could serve a purpose. Don Julián Ibarra and El Güero Eliso were the team’s coaches. They went to talk to her Dad and talked him into letting La Maya play. Every Sunday the old stadium would fill up. Most of the spectators were train workers who came to watch the women. The stadium was made of wood. The catcher, Juana Lerma, asked La Maya to pitch softer, but she told her to go to hell and learn to catch.

They named La Maya pitcher on that very first day. It was the first time she felt she could be successful, break barriers, that her restlessness could serve a purpose. Don Julián Ibarra and El Güero Eliso were the team’s coaches. They went to talk to her Dad and talked him into letting La Maya play. Every Sunday the old stadium would fill up. Most of the spectators were train workers who came to watch the women. The stadium was made of wood. The catcher, Juana Lerma, asked La Maya to pitch softer, but she told her to go to hell and learn to catch.

One day La Maya told El Güero that she didn’t want to pitch anymore, because it tired her out and she had to work in the mill. He was smart and offered her ten pesos for every game she pitched, as long as she didn’t tell anyone else. Since her pay for her full-time job was seven pesos a week, her side job, which she enjoyed, provided a huge salary!

There were three women’s teams in that era: Cigarrera La Conquistadora, Molino del Valle, and Cervecería Díaz de León, La Maya’s team. They won the championship and got a silver cup donated by Casa Huerta, a local artesanías shop. That was 1928. To get into the stadium cost 30-50 centavos. La Maya recalls that was the year the women in England got the vote.

She remembers participating in exhibition games in Hermosillo. And that one day El Güero Eliso bet her 50 pesos that she couldn’t ride the wild horse that grazed on the lot where they practiced baseball. She mounted the horse in one jump, and and proceeded to ride him calmly around the lot. El Güero didn’t realize she had learned how to ride while living in the country as a kid.

In 1931 La Maya still played baseball and was well know for her batting and pitching. She liked the fame, that she was important to people. One day some people told her about a boxer who was looking for someone in Mazatlán to fight. She’d always liked a challenge, so she got to thinking, “I’m good at baseball; how about boxing? What would happen if I put on the gloves?” She knew the boxer was training in Playa Sur, near the balnearios on Alemán. La Maya went to watch her; there were many spectators. “I can beat her,” she thought. She knew her muscular arms were strong, and decided to do it. She was ecstatic when the organizers said they’d pay her 150 pesos to fight! El Güero was her manager, and the promoter was Chano Gómez Llanos. She had a month to get ready and trained with Kid Milo, Mike Rubí, Benjamín Pérez, El Borrego Torres and Mike Herrera who helped her a lot.

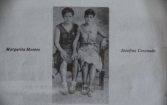

In the days leading up to the fight everyone was talking about it; two women, boxing! The lady’s name was Josefina Coronado, and her manager was the Cuban Roberto Negro Molinet. She never expected the type of rival that La Maya would be. Tickets sold out for the fight in Teatro Rubio, today the Angela Peralta. She was nervous at first: three floors full of screaming people. The fight was four rounds and she felt she dominated; La Maya won by decision. The main fight of the evening was between Mike Herrera and Joe Conde, the Dandy of the Ring.

La Maya tells us that once the bantam weight champion, Raúl Talán, came to fight Joe, fresh from Japan where he’d been traveling. He watched her train, congratulated her, and gave her some gifts. They remained friends for years; she visited him in Mexico City when he was retired and wrote for El Nacional. He interviews La Maya several times. Joe Conde was her sparring partner. He was a fine boxer. Joe was a gentleman in and out of the ring. Elegantly dressed with a cane and bowler hat. It was the era of the famous Zurita-Casanova-Joe Conde triangle.

In 1931 La Maya traveled to Nogales to box, with permission from her employer, Mr. del Valle. Even though she went for three days, the trip ended up lasting three months. By then her brother Pepe was her manager. She was fighting men and winning by knockouts. She traveled to Tucson to fight and toured Nayarit.

La Maya remembers going to the mascarade ball for Carnaval in the As de Oros. Her brother Pepe chaperoned her. Someone got into a fight with him, she jumped to defend him, and everyone said “a little masked lady” had knocked the guy out! It was quite the scandal.

La Maya tells us she never looked for a fight. She traveled all over and made 150 pesos a fight touring Sonora, Nayarit, Sinaloa, Arizona, Baja California. She had 33 professional fights, five against women and 28 vs. men. She was the first woman boxer to fight against US American men and won the Pacific Coast Championship when she beat Josefina Coronado.

In 1933 she had a boyfriend, the son of a German and a Mexican, a very handsome guy with whom she’d had a five-year relationship. It was hard for them, because she traveled a lot. One time at a bull fight the people asked La Maya to fight. He said he didn’t want to see her do it, but she did it anyway. She punched the bull several times to much applause.

Several days later General Juan Dominguez came to La Maya’s house to ask her to become a bullfighter. María Cobián was coming, nicknamed La Serranito, and he wanted her in the ring, too. “You have good legs to run if you have to.” They paraded in a convertible before the fight, accompanied by a banda sinaloense. The fight was in Plaza REA, where the Angel Flores school is now. They paid La Maya 250 pesos. But she tells us she was scared when the bull came out. People shouted at her to stick him with the banderillas. She got one in, but the other went into his butt. Her boyfriend was in the first row, applauding. That would be the last corrida that La Maya did formally, as she didn’t want to play with bulls anymore; they frightened her.

A while later she saw her boyfriend in the theater with another girl. For the first time in her life she was hit with disillusion; it was like a knockout. She broke off their relationship right then and there; La Maya’s blood would never mix with German blood.

In 1939 La Maya married José Valdez Alvarez. He was a stevedore on the docks. They saved enough money together to buy a cargo truck that they used for hauling. They had three sons: José, Alejandro and Efraín, but the youngest would be the only one to survive. At the time the book was published Efraín was married with three kids, her grandchildren Efraín, Alfonso and Alicia Margarita.

In 1939 La Maya married José Valdez Alvarez. He was a stevedore on the docks. They saved enough money together to buy a cargo truck that they used for hauling. They had three sons: José, Alejandro and Efraín, but the youngest would be the only one to survive. At the time the book was published Efraín was married with three kids, her grandchildren Efraín, Alfonso and Alicia Margarita.

In 1948 La Maya returned to work in the mill but because the pay was so low she decided to also open a bicycle repair shop. Pepe her brother helped her. They rented bikes for 40 cents an hour. She came and went on bike from El Venadillo every day, which kept her legs in good shape. She would race to Villa Unión on bike sometimes, always against guys.

After tiring of bicycles she put in a tortillería, and then changed that for a mechanic’s shop. When she sold that Mr. Valeri Saracco paid her with a Studebaker. With that she started to haul pigs; people were impressed with how easily she lifted them into the truck.

La Maya always worked hard and could learn how to do anything. She had lots of victories and triumphs. She believed she led the way for many women athletes, especially on the Pacific Coast. She was good at weight lifting and all sports, and wonders if perhaps she could have gone to the Olympics.

La Maya tells us of the satisfaction she felt appearing in several magazines, including Ripley’s Believe it or not. On March 11, 1988, the reporter Michell Chemin from the French magazine Liberation‘s sport section published an article on La Maya.

La Maya tells us of the satisfaction she felt appearing in several magazines, including Ripley’s Believe it or not. On March 11, 1988, the reporter Michell Chemin from the French magazine Liberation‘s sport section published an article on La Maya.

She closes the booklet by saying that, “Now, at 92 years of age, with my physical and mental abilities intact, I look back on my life with nostalgia and feel I was born in the wrong era.”

Now you know a bit of the story of La Maya. Please pass it on; we shouldn’t let this woman’s legacy die out!

Delfina worked with her at the mill and lived near the baseball stadium, where the Escuela Nautica is now. She insisted La Maya go with her to play baseball, but La Maya’s dad wouldn’t let her. She then invited a neighbor to go with her one afternoon, and they went without telling anyone. The team members loaned La Maya a real glove that fit so well, and a real ball that caressed her hand, unlike what they had in the barrio.

Delfina worked with her at the mill and lived near the baseball stadium, where the Escuela Nautica is now. She insisted La Maya go with her to play baseball, but La Maya’s dad wouldn’t let her. She then invited a neighbor to go with her one afternoon, and they went without telling anyone. The team members loaned La Maya a real glove that fit so well, and a real ball that caressed her hand, unlike what they had in the barrio. They named La Maya pitcher on that very first day. It was the first time she felt she could be successful, break barriers, that her restlessness could serve a purpose. Don Julián Ibarra and El Güero Eliso were the team’s coaches. They went to talk to her Dad and talked him into letting La Maya play. Every Sunday the old stadium would fill up. Most of the spectators were train workers who came to watch the women. The stadium was made of wood. The catcher, Juana Lerma, asked La Maya to pitch softer, but she told her to go to hell and learn to catch.

They named La Maya pitcher on that very first day. It was the first time she felt she could be successful, break barriers, that her restlessness could serve a purpose. Don Julián Ibarra and El Güero Eliso were the team’s coaches. They went to talk to her Dad and talked him into letting La Maya play. Every Sunday the old stadium would fill up. Most of the spectators were train workers who came to watch the women. The stadium was made of wood. The catcher, Juana Lerma, asked La Maya to pitch softer, but she told her to go to hell and learn to catch.

In 1939 La Maya married José Valdez Alvarez. He was a stevedore on the docks. They saved enough money together to buy a cargo truck that they used for hauling. They had three sons: José, Alejandro and Efraín, but the youngest would be the only one to survive. At the time the book was published Efraín was married with three kids, her grandchildren Efraín, Alfonso and Alicia Margarita.

In 1939 La Maya married José Valdez Alvarez. He was a stevedore on the docks. They saved enough money together to buy a cargo truck that they used for hauling. They had three sons: José, Alejandro and Efraín, but the youngest would be the only one to survive. At the time the book was published Efraín was married with three kids, her grandchildren Efraín, Alfonso and Alicia Margarita. La Maya tells us of the satisfaction she felt appearing in several magazines, including Ripley’s Believe it or not. On March 11, 1988, the reporter Michell Chemin from the French magazine Liberation‘s sport section published an article on La Maya.

La Maya tells us of the satisfaction she felt appearing in several magazines, including Ripley’s Believe it or not. On March 11, 1988, the reporter Michell Chemin from the French magazine Liberation‘s sport section published an article on La Maya.

Gabriel Alfonso Gamez Zuñiga is Mazatlán’s resident clock whisperer, an incredibly talented, personable guy who is the last of a dying breed—the keeper of knowledge and skill that is nearing extinction.

Gabriel Alfonso Gamez Zuñiga is Mazatlán’s resident clock whisperer, an incredibly talented, personable guy who is the last of a dying breed—the keeper of knowledge and skill that is nearing extinction.