We had a FANTASTIC afternoon and evening learning about shrimping with a cast net/atarraya in the estuaries of Agua Verde, which is between Caimanero and El Rosario. We returned home with heartfelt smiles, new friends, 5 kilos of huge fresh shrimp (for which we paid about 7 bucks), a bunch of fresh crab (which our new fishermen friends gave us for free), and a bucketload of end-of-season mangoes ($4 for a crate full). ¡¡Viva Sinaloa y los Sinaloenses!!!!!!

We set out late Saturday afternoon with our compadres, Jorge and Silvia, to attend the first annual “Festival de la Frasca.” While Jorge told me “frasca” is not a word, and that I surely must be trying to say “zafra” or “open season,” local people tell us it is a southern Sinaloan term meaning “to capture shrimp from the estuary.”

The Festival de la Frasca was supposed to be a food fest with live music. But as usual they were running late setting up, and before we could really get into the party we found much more exciting things calling us.

Just one month ago we had driven this very same road, but shrimp season is now open, and it was an even more wonderful place! I HIGHLY recommend you visit during shrimping season! While the season lasts 6 months, the first few weeks are supposedly the best, as the shrimp and the shrimpers are the most plentiful.

As we drove in we saw men with cast nets (atarrayas) everywhere. Though mango season has finished, it is now the height of the shrimping season, and they have already planted tomatoes. After tomato season will come chile season, and so goes the year here.

Shrimp season is huge. We were told that opening day is like Carnaval—wall-to-wall people everywhere, with families fishing, picnicking and partying all night long. Family members come from all over the region back to Caimanero and Agua Verde to help with the shrimping, and to perform their obligations under the cooperativa(to work a minimum of so many hours and to capture a minimum of so many kilos). Women and children hang out with the fishermen, so it feels like life transfers from town to the estuary during this time.

Shrimp season is huge. We were told that opening day is like Carnaval—wall-to-wall people everywhere, with families fishing, picnicking and partying all night long. Family members come from all over the region back to Caimanero and Agua Verde to help with the shrimping, and to perform their obligations under the cooperativa(to work a minimum of so many hours and to capture a minimum of so many kilos). Women and children hang out with the fishermen, so it feels like life transfers from town to the estuary during this time.

Beside the road that just two weeks ago looked so very different we saw little houses or shelters, many of them housing the shrimpers. A standard shelter like the one shown here has one or two lights powered by a propane tank, a plastic shelter for rain, chairs, a way to cook (usually a fire pit), a radio and a cell phone. As you can see, they sit just off the road. Can you imagine spending the night there with cars, trucks, and motorcycles coming by a few feet away from you all night?

We greeted one of these guys, Rodolfo, at one of the stands, and he urged us to pull over and join him. So we did. The night crew, including Marco (who lives in Mazatlán but returns home for shrimp season), his 8 year old son and his 17 year old nephew, plus one other man, were just pulling up as we arrived.

Rodolfo proceeded to feed us a whole mess of fresh crab and shrimp, beside the road, in the fresh breeze, looking out over the estuary. La vida dura. While I well know, from living in Japan, how to crack open a fresh crab, scrape out the lungs, and eat the juicy brain and meat, this fisherman really enjoyed teaching us, and my comadre, Silvia, really enjoyed learning.

Here we also ate shrimp crudo with salt and lime (my all-time favorite—huge prawns, still wiggling; oh yum!), but he also cooked some for Silvia in a pot of broth.

We stayed here about an hour, chatting, feasting and just generally relaxing. We bought our first few kilos of shrimp, as well as receiving a huge bagful of cooked crab.

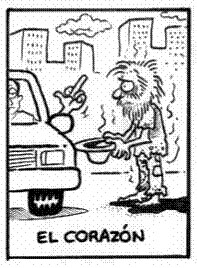

There were also many changueros, who we’ve heard about since arriving in Mazatlán, but this was the first time we met a few. They are estuary shrimpers who are not members of a cooperativa. They catch shrimp but legally are not supposed to be doing so. Many of the changueros used purina (shrimp chow) to get the shrimp up to the surface. None of the cooperativa fishermen we met used purina. They were very proud to explain to us that their shrimp were the purest.

Below is a video of one shrimper casting a net, and his wife helping him take out the shrimp and put them into a bucket.

After getting back in the car, we made the rounds of several cooperativas. At the first one the view was spectacular.

Rodrigo, a man we met there, sold us some more live shrimp. At left is his photo, and below a video of some of the shrimp wishing they could run away.

We had arrived here just in time for sunset. The sky and the water glowed. People were all so friendly, open and hospitable that it was amazing. Everyone was eager to talk, to explain this long Sinaloan shrimping tradition, and to share their catch of the day with us. To me this frasca tradition is soooo important; it’s Sinaloa’s history, and the if not some of the best shrimp in the world. And tons of it are harvested BY HAND here each year and shipped worldwide. I know such shrimping used to happen right here in Mazatlán; even next to Hotel Playa was an estuary (no wonder Zona Dorada floods).

The fishermen brought out packets of salt, fresh limes and bottles of salsa, and urged us to eat from their catch to our hearts’ content. Alfresco dining overlooking the estuary with friendly, happy, relaxed, knowledgable people; it was a wonderful afternoon. Every boy we met knew how to cast a net. They seem to start as young as seven or eight.

We also sat here for quite a long time, again feasting on raw shrimp (no cooked ones this time), and watching the guys cast their nets in the scenic little harbor.

The video below shows a guy casting his net from a panga, so you can see that as well as the earth-bound approach shown above.

The pangas or small fishing boats go out with two guys normally, one remero or rower, and one atarrayero or net caster. Most of the estuary is only hip- or waist-deep, so the remero carries a long stick or remo and basically pushes the panga along, similar to the movement of the gondolas in Venice.

Below is a short clip of the gentleman at left rowing.

There are various cooperativas to which the shrimpers belong. This drive out to one of them was really something — estuary on either side of the road, with loads of lit pangas all around.

Below is a video, so you can get a better feel for this road-with-water-on-both-sides drive.

After visiting some very cool places and meeting lots of wonderful people, we ended up spending another couple of hours sitting with Marco and his family. It was so peaceful there, and so very pleasant. Excuse the poorer quality of the photos from here on. The batteries on our camera died, so the remaining photos are taken with our phone.

On the way out we stopped at one last cooperative, this one the largest we’d seen. Here they had a large building or warehouse, surrounded by dozens of pangasfishing. Families were sitting and standing everywhere, waiting for their husbands, fathers, boyfriends and brothers to come in with their catch.

A semi-truck full of ice was waiting nearby.

A group of men with a scale and ledgers was registering incoming shrimp.

After dipping the bins full of shrimp into ice water, they placed the bins in the refrigerated truck where they are covered with ice and then taken to Mazatlán for sorting, packing and export.

It was at this last cooperative that we also saw our youngest atarrayero, this boy of about eight, at left.